Eigenvectors

Definition

An eigenvector is a nonzero vector $\vec{v}$ such that there exists a scalar $\lambda$ so that $A \vec{v} = \lambda \vec{v}$. The $\lambda$ is known as an eigenvalue, and together they form an eigenpair

Alternatively, an eigenvalue is a value $\lambda$ such that $|A - \lambda I| = 0$.

An eigenvector of a linear transformation $A$ is a vector whose direction doesn't change when a transformation is applied. What may change is its magnitude, which is scaled by the eigenvector's corresponding eigenvalue.

The notation that will be used for this article will be to denote the ith eigenvalue of $A$ as $\lambda_i$ and the ith eigenvector as $\vec{v_1}$.

Properties

- $\forall_i\ |A - \lambda_i I| = 0$

- Eigenvalues are the roots of the characteristic polynomial

- If a matrix has $n$ distinct eigenvalues, it must have $n$ linearly independent eigenvectors

- $|A| = \Pi_{i=1}^n \lambda_i$

- A matrix is invertible iff every eigenvalue is nonzero

- tr$(A) = \Sigma_{i=1}^n \lambda_i$

- The eigenvectors of $A^n$ are the same as those of $A$; it's eigenvalues are $D^n$

- if $B$ has the same eigenvectors as $A$, then $AB$ has the same eigenvectors as $A$, and its eigenvalues are the product of $A$ and $B$'s eigenvalues

Diagonalizable

A matrix is diagonalizable if it can be written as $A = VDV^{-1}$, where $D$ is a diagonal matrix. This has a strong connection to eigenvalues/vectors, because (if diagonalization is possible) $V$ is a matrix of $A$'s eigenvectors, while $D$ is a matrix with $A$'s eigenvalues:

\[ V = \begin{bmatrix} \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \vec{v_1} & \vec{v_2} & \dots & \vec{v_n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \end{bmatrix} D = \begin{bmatrix} \lambda_1 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_2 & \dots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & 0\\ 0 & 0 & \dots & \lambda_n \\ \end{bmatrix} \]If $A = VDV^{-1}$, then $D$ and $A$ are similar, which means that (in some sense) $D$ and $A$ capture the same linear transformation, just in different bases. This means that $A$ can be described as changing bases, applying a scaling (since $D$ is diagonal), and then changing back to the original basis.

If a matrix is diagonalizable, then we can find non-integer powers of it. Note \[ A^m = (VDV^{-1})^m = VD^mV^{-1} \] So the find $A^m$, we only need to raise each diagonal entry of $D$ to the power of $m$, and then apply $V$ and $V^{-1}$. This means that $A^m$ has the same eigenvectors as $A$, and all of its eigenvalues are the eigenvalues of $A$, raised to the mth power.

Defective

A matrix that cannot be diagonalized is called defective, which is true if (and only if) it doesn't have $n$ distinct eigenvectors. Intuitively, Defective matrices apply a "sheer", and so cannot be represented by combinations of rotations, scalings, and reflections. The good news is that defective matrices are "rare". Consider:

\[ A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0\\ 1 & 1 & 0\\ 1 & 1 & 1\\ \end{bmatrix} \]All three of it's eigenvalues are 1, and it only has one (non-zero) eigenvector: \[ \vec{v_1} = \vec{v_2} = \vec{v_3} = \begin{bmatrix} 1\\ -1\\ 1\\ \end{bmatrix} \]

As a result, we can't use $V$ to form a (complete) basis, so we can't express $A$ as $VDV^{-1}$. In fact, this implies that there is no way to diagonalize $A$.

Iteration

From viewing a matrix as simply a change-in-basis, then a scale, and then returning to the original basis, eigenvectors capture the long term behavior of applying a matrix repeatedly to a vector. In fact, $AAA...AA\vec{v}$ is guaranteed to converge to some eigenvector of $A$ — almost always the one with the largest eigenvalue.

Below is a demo that lets you you drag two green vectors. These are the eigenvectors of the transformation, and their lengths are their corresponding eigenvalues. The demo applies the transformation to every (red) vector multiple times. Note how every vector tends to become more similar to the largest eigenvector's direction as we apply more iterations.

Spectral Norm

The spectral norm of a matrix is defined as: \[\rho(A) = max\{|\lambda_1|, |\lambda_2|, ... ,|\lambda_n|\}\] As you have seen, the long-term behavior of applying a matrix depends almost entirely on the largest (in absolute terms) eigenvalue and its corresponding eigenvector. In fact, we have the following theorem: \[\rho(A) < 1 \iff \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} A^n = 0\]

As well as: \[\rho(A) > 1 \iff \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} ||A^n|| = \infty\]

Which claims that the spectral radius determines whether the matrix will force (nearly) every point to converge to zero, or to grow without bound.

Another theorem is Gelfand's Formula, which states that for any matrix norm $||\cdot||$

\[ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} ||A^n||^{1/n} = \rho(A) \]

Spectral Gap

The spectral gap of a matrix is defined as the difference between the (moduli of the) two largest values, and is useful as a measure of how long it takes for points to converge. The larger the gap, the more quickly points will converge to the largest eigenvector.

Imaginary Eigenvectors

The demo above demanded real eigenvectors, but what if we have a real matrix with imaginary eigenvectors? Every time we multiply a real vector by a real matrix, we get a real vector, so how are we ever going to converge to a complex eigenvector?

The answer is: we don't. Instead, there is a very curious phenomenon:

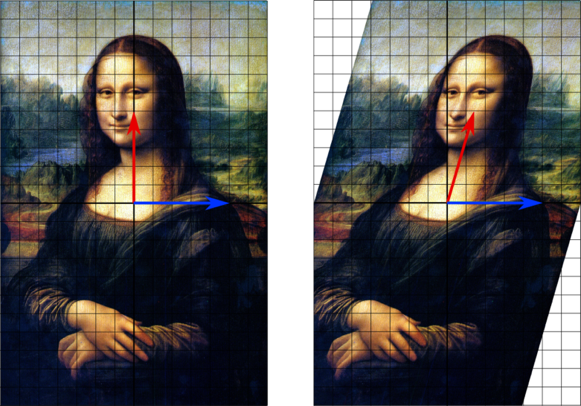

The points spiral! Depending on the exact eigenpair, the points may spiral inwards and converge on (0, 0) or diverge outwards to infinity (as shown above), but this spiraling behavior is consistent for imaginary-eigenvectored matrices.

Using Eigenvectors to Solve Linear Differential Equations

The notation of eigenvectors/values need not be confined solely to $\mathbb R^n$ or $\mathbb C^n$, but can be extended to vector spaces of infinite dimension or even functions. For example, let D be the linear differential operator - that is $D(f)$ is the derivative of $f$. It seems natural to ask what the eigenvectors of D are - that is, for what function(s) does \[ f'(x) = D(f) = \lambda f(x) \] This is satisfied by $f(x) = e^{\lambda x}$, which functions as the eigenfunctions of $D$.